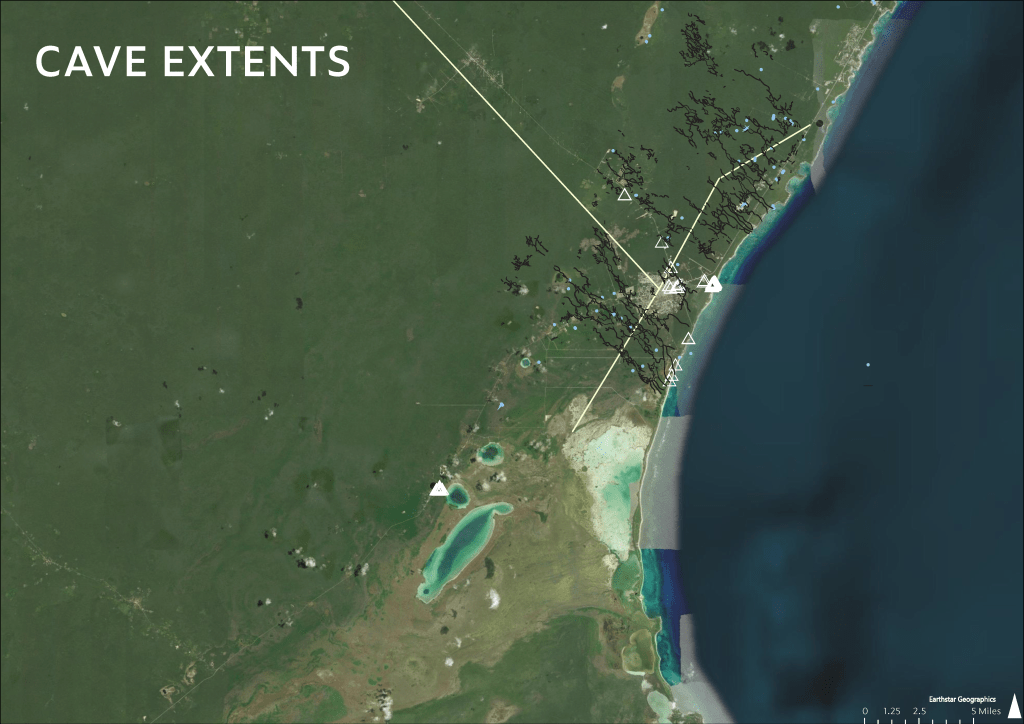

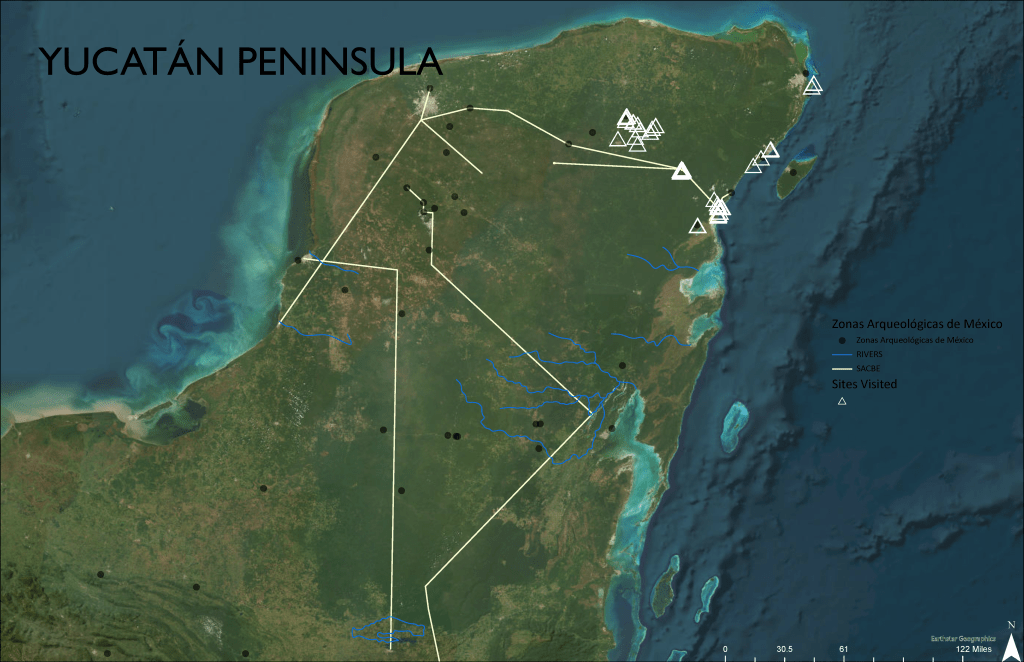

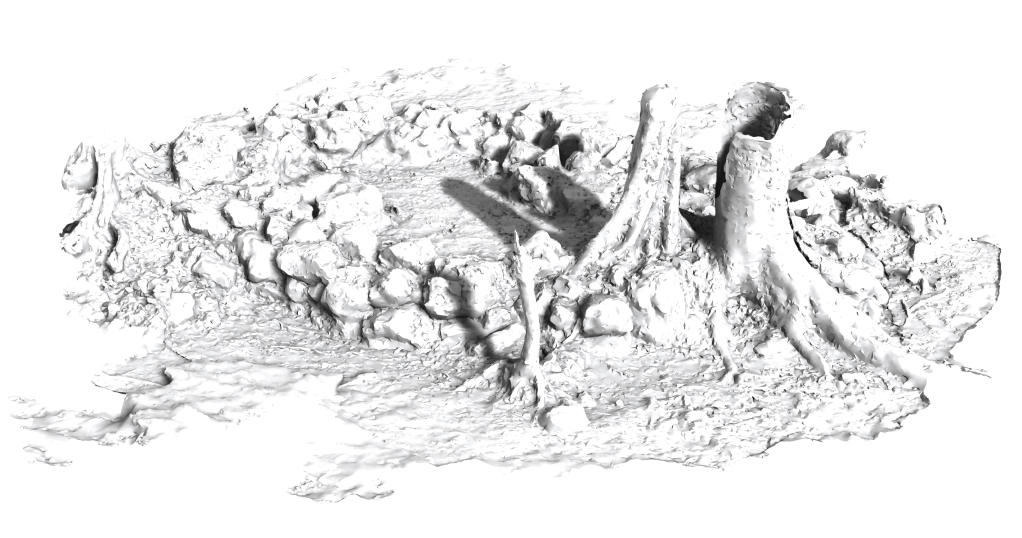

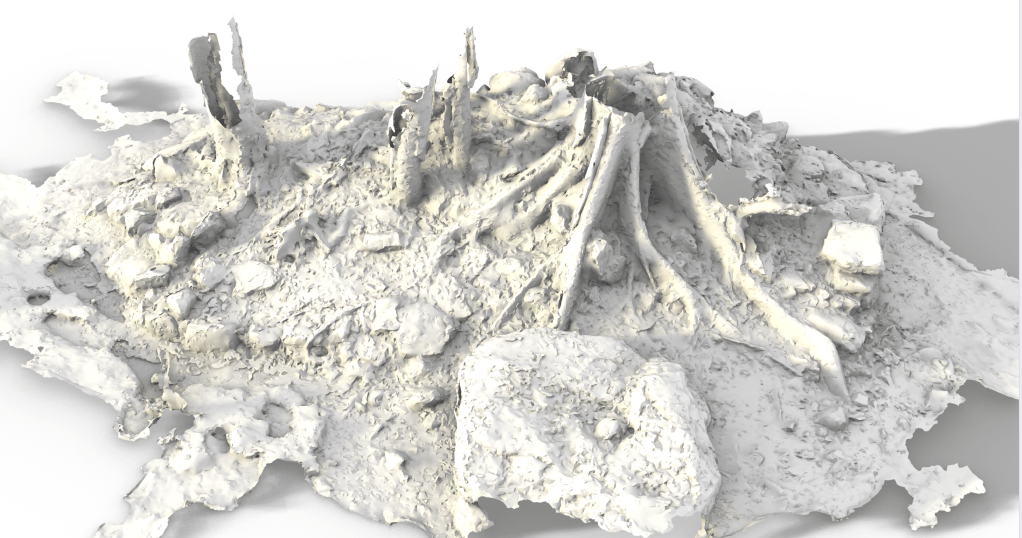

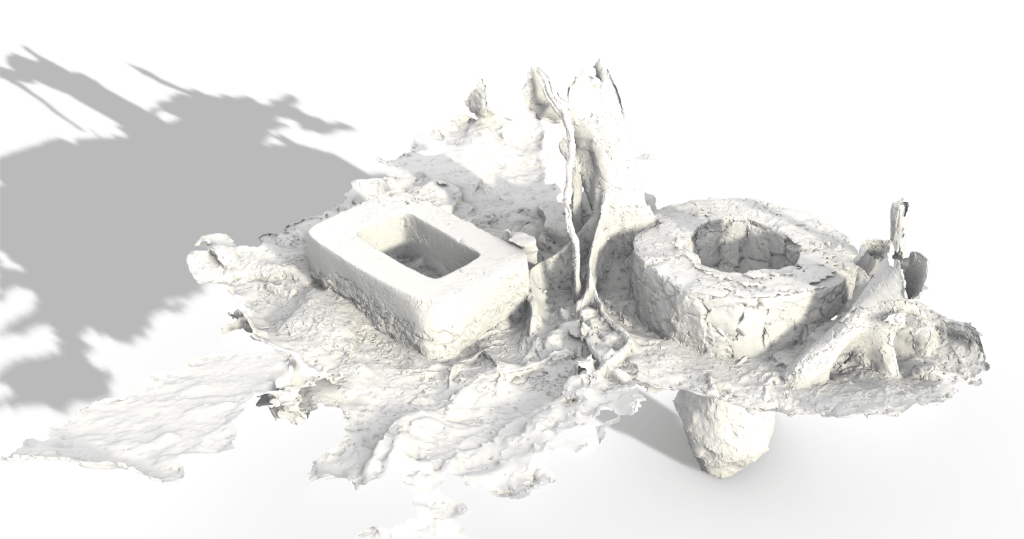

The jungle of the Yucatán Peninsula, Mexico, is home to hundreds of ruins of the advanced Stone Age society of the Maya, inclusive of cities connected by extensive road networks and water infrastructure systems. As climate change prompts designers to take closer looks at vernacular landscapes, this thesis presents a set of case studies of the pre-Columbian vernacular landscape of the Mayan cities Tulu’um, Ek’Balam, and Kob’áh that illustrate how these settlements were designed to capture and store potable water. The Maya engineered integrated runoff management systems into the city that captured and retained rainwater into chultuns, aguadas, and reservoirs, and thus guaranteed water access during all seasons. In addition to critical site maps of the water management systems, the case studies consist of a literature review of the sociopolitical history of the region and photogrammetry models of sample reservoirs and wells. In situ observations and photographic records describe the remnant materiality of these vernacular designs, which used simple clays to ensure the waterproofing of locally sourced stone structures. The sophistication of the masonry that created these structures is evident in the stability of the ruins, and is visually testified in the detailed three-dimensional models produced by photogrammetry. The resulting study links the water infrastructure to a highly sophisticated integration of the physical structure of the landscape with built form that can serve as a model for efficient and sustainable contemporary water infrastructure systems that respond to seasonal changes in water availability.